CANADA, AN ARTISTIC YET TOO TRADITIONAL LAND

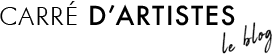

Forty years after its unification by the Confederation of 1867, Canada is in the process of defining its own political, economic and social identity.

While its influence is increasing on the world chessboard, in the artistic and cultural field however, the country whom symbol is the maple leaf is way behind. Still enslaved by the pictorial traditions of the Old Continent, Canadian painting is strongly influenced by conventions and European taste.

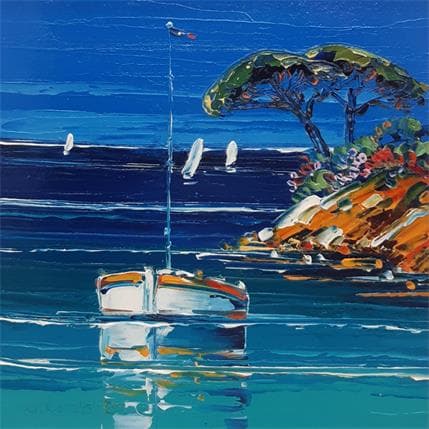

Landscape art has existed for decades, and despite the opening of the Canadian Pacific Railway's transcontinental railway, which allows access to the Prairie and Rocky Mountains, it is mainly featuring simple representations made through the sibylline European academic prism. In this frozen and moribund atmosphere, the first sparks of an announced change are lit by Maurice Cullen and James Wilson Morrice, who were among the first artists to apply the principles of French Impressionism to Canadian landscapes.

The real flame will come from a small group of painters who meet in Toronto in the early 1910s to present their respective works, their inspirations and to think of way out for Canadian art.

While its influence is increasing on the world chessboard, in the artistic and cultural field however, the country whom symbol is the maple leaf is way behind. Still enslaved by the pictorial traditions of the Old Continent, Canadian painting is strongly influenced by conventions and European taste.

Landscape art has existed for decades, and despite the opening of the Canadian Pacific Railway's transcontinental railway, which allows access to the Prairie and Rocky Mountains, it is mainly featuring simple representations made through the sibylline European academic prism. In this frozen and moribund atmosphere, the first sparks of an announced change are lit by Maurice Cullen and James Wilson Morrice, who were among the first artists to apply the principles of French Impressionism to Canadian landscapes.

The real flame will come from a small group of painters who meet in Toronto in the early 1910s to present their respective works, their inspirations and to think of way out for Canadian art.